Three Theories of Buy Now Pay Later (BNPL) Loans

BNPL is rapidly growing in practice, but how does it work in theory?

These days, when you check out from an online retailer, you’re likely to see an option to pay using Buy Now Pay Later (BNPL). Offered by companies such as Affirm, Klarna, and Cash App Afterpay, these loans allow you to split the total cost into four installments, one due immediately and the others due at two-week intervals over the next six weeks. BNPL lenders earn a transaction fee of 3-8% from the merchant and can make additional money from consumers in fees.1

In recent years, BNPL has rapidly expanded in the U.S. market, growing from $2 billion in transaction volume in 2019 to over $115 billion in 2023 and counting.2 In 2023, roughly 20% of U.S. consumers used BNPL at least once, with 20% of those users paying with BNPL more than once per month.3 While BNPL transaction volume is still small relative to credit card transaction volume, which was $4.88 trillion in 2022, BNPL is well on the way to becoming a sizable segment of the consumer financial marketplace.

But how does it work in theory?

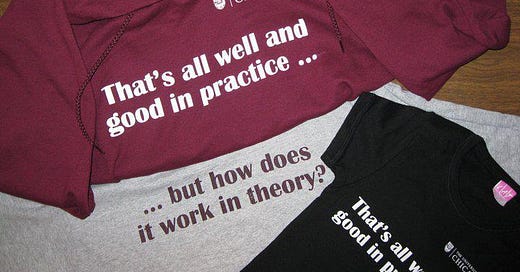

Walk around the University of Chicago campus, where one of us taught for 8 years, and you’ll invariably see someone wearing a “That’s all well and good in practice… but how does it work in theory?” T-shirt. With BNPL’s rapid rise, we’ve been asking ourselves this very question. Here are three theories of BNPL:

Interest rate arbitrage by non-credit-constrained consumers. BNPL allows non-credit-constrained consumers to exploit the spread between their return on assets and the interest-free BNPL loan during the six-week payoff period.

Credit expansion to consumers who face high interest rates or can’t get a loan. Unlike credit card issuers, BNPL lenders can target loans based on product or merchant characteristics (e.g., someone buying home office furniture versus booking a hotel room in Vegas), potentially allowing them to extend credit to lower default risk consumers who face high interest rates or can’t get a loan through other channels.

Bite-sized payments to psychologically help consumers overcome sticker shock. BNPL allows consumers to overcome the sticker shock of a large upfront payment, splitting the total cost into seemingly more manageable biweekly payments.

While the BNPL interest rate arbitrage exists, the benefits are small and not large enough to overcome the transaction costs typically found in the consumer financial literature. To see this, suppose you’re considering buying an $800 couch using BNPL. Let’s say your high-yield savings account pays you a generous 5% APR. If you pay off the couch over time using BNPL versus buying the couch in cash upfront, you’d earn only $2.31 in additional interest on your savings.4 And if your counterfactual to BNPL is buying the couch with a credit card that you pay off in full each month, the “float” you receive on your credit card will nearly always save you more than the BNPL loan.5

Another knock on the interest rate arbitrage theory is that it’s hard to see how merchants and lenders benefit from this use case. Merchants have no incentive to pay a cut to BNPL lenders for consumers who would otherwise have the resources to make the purchase. Without the transaction fees and with limited late fee potential from non-credit-constrained consumers, there is no clear way for BNPL lenders to make money.

The credit expansion theory offers clearer benefits for lenders and merchants. Merchants should be willing to pay the fees since they enable sales to credit-constrained consumers that would otherwise not occur. As mentioned, BNPL lenders may have a credit provision edge since, unlike credit card issuers, they can condition loans on the product or merchant. They may also be able to claw back the product if payments are not made, as was the case with Coachella tickets this past year. And if the credit card market is any guide, BNPL lenders will be able to earn additional revenue from late and other fees from this borrower segment.

Consumers, too, could benefit from lower interest rates and increased credit access from BNPL loans. The natural concerns are that BNPL leads to an over-expansion of credit and a proliferation of hidden fees, trapping consumers in debt and creating broader risks for financial markets and the economy.

We’re intrigued by the bite-sized payment theory as an explanation for the rapid growth of BNPL. It’s not a rational theory: For a non-credit-constrained customer, the present value of paying upfront or over 6 weeks is virtually indistinguishable. But spreading out payments over six weeks isn’t obviously problematic either. Without taking a strong stand, it’s hard to know whether you “should” have made the purchase or not.

Monitoring and shaping a new market

Our understanding of the BNPL market is still in its early stages. The most comprehensive analysis we’ve seen is this report from the CFPB, but the data only runs through 2022 and may not catch emerging trends in the industry. The recently announced credit bureau reporting by Affirm and two unnamed lenders will allow us to track more recent trends, but is limited in its coverage.

The concern is that BNPL evolves in ways that lead consumers to overextend themselves, with burdensome fees and debt payments for consumers, and potential risks for the financial sector and broader economy. To this end, a new study by my colleague Ed deHaan, along with Jungbae Kim, Ben Lourie, and Chenqi Zhu, is sobering. Using detailed transaction data for over 10 million consumers, and a clever research design based on BNPL adoption at regularly visited retailers, they find that new BNPL loans significantly increase bank overdraft charges, along with credit card interest and fees.

On the other hand, the expansion of BNPL could represent healthy innovation in our consumer financial sector. The credit card industry famously suffers from a failure of competition and high fees that have only been partly addressed by regulation. To the extent that BNPL provides competition for the credit card industry and responsibly extends access to credit to underserved borrowers, it would be welcome.

Making sure BNPL evolves in a pro-consumer manner requires monitoring and possibly new consumer protection rules. In 2024, the CFPB issued an interpretive rule confirming that BNPL providers are subject to the same oversight as credit card providers. However, the Trump administration has said it would not “prioritize enforcement actions” against BNPL lenders, limiting the federal government's ability to monitor and regulate the industry. To prevent us from flying blind, researchers will need to step up their game, analyzing market trends and conducting careful studies of the consequences of BNPL. This research, together with evidence-based policymaking as necessary, can help ensure BNPL has the maximum benefit for markets and consumers.

200×((1+0.05/365)14−1)+200×((1+0.05/365)28−1)+200×((1+0.05/365)42−1)=$2.31

Credit card billing cycles are 28-31 days, and payments are typically due after a 21-day grace period. So if you buy the couch on the last day of the cycle, meaning you pay it off 3 weeks after that purchase from the same high-yield savings account, your savings from the float will be 800×((1+0.05/365)21−1)=$2.30 which is virtually identical to the $2.31 from using BNPL. Purchasing at any point earlier in the cycle would generate larger savings.