The Folly of CFPB RIP

Why Trump’s attempt to dismantle the CFPB is bad policy and could provoke a backlash

In the aftermath of a global financial crisis triggered by risky subprime mortgage lending, Congress created the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. The CFPB was designed to address the diffusion of responsibility for consumer financial markets across too many regulators with too many competing priorities. The solution was to centralize regulation and enforcement under a single agency with a singular focus on consumer protection and enhancing the function of consumer financial markets.

I was in graduate school at the time and was searching for research topics. I was drawn to consumer finance because of the tremendous toll that financial distress imposes on families. As I later put it, I wanted to study the other 1% – those with the least power and wealth in our society – out of the belief that well-designed policy could reduce the frequency and burden of the financial shocks they faced.

From that point onwards, a primary line of my research has involved consumer financial markets, financial distress, and medical debt. In addition to my research and teaching, I worked on consumer protection and medical debt policy at the White House National Economic Council in 2022-2023 and have served on the CFPB Academic Research Council since 2023.

Based on my scholarship and experience, I believe the CFPB has been a major force for good. As I’ll detail below, the agency has been instrumental in shifting banks away from a fee-based revenue model, reducing the credit market burden of medical debt, and stopping countless financial scams. Given this, the Trump Administration’s efforts to dismantle the CFPB are a big step backward for economic policy and could provoke a backlash that the White House may come to regret.

Shifting banks away from a fee-based revenue model

The CFPB came into existence around the same time as two major transformations in economic research, which shaped my views of CFPB policies.

The first was the mainstreaming of behavioral economics. For people like me, who were primarily interested in policy and markets, exposure to behavioral economics gave us the toolkit to analyze consumer financial regulation in a rigorous manner.

That is, we could build models that combined behavioral features of consumers (such as time inconsistency, inattention, and inertia) with problematic features of the market (such as teaser rates loans, hidden fees, and limited search and switching) to quantify the welfare loss under the status quo and the potential welfare gains from policy remedies.

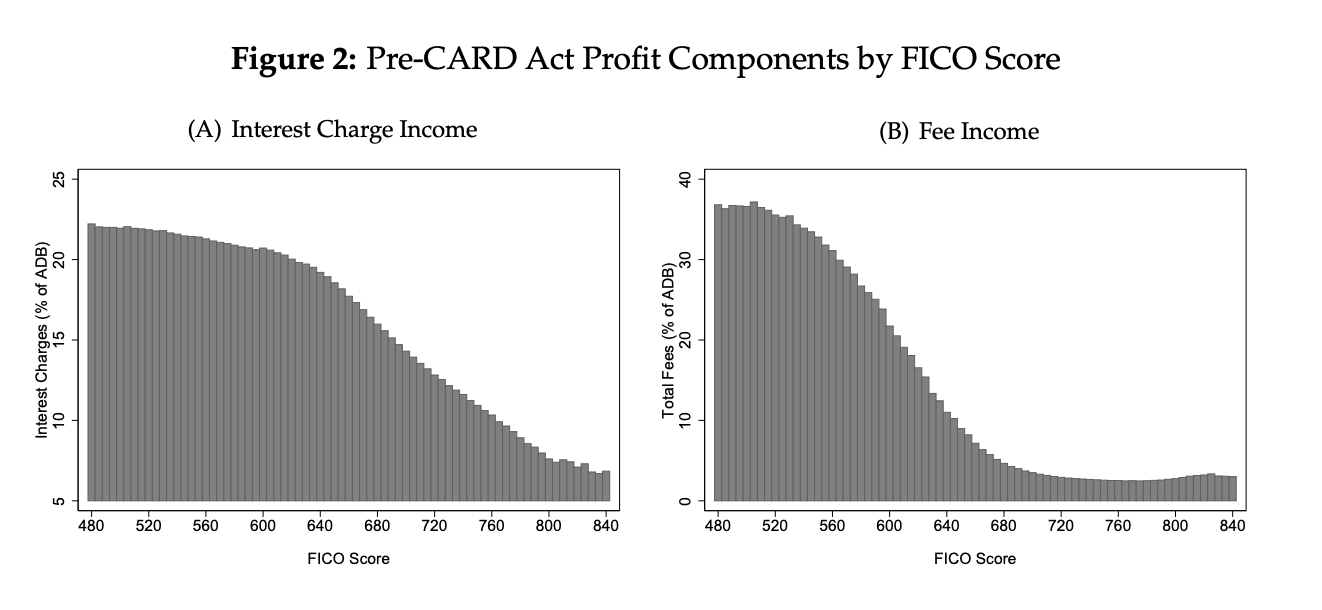

The second factor that shaped my views of CFPB policy was the exposition of big data. These data showed that banks were making a shocking amount of their revenue not from interest charges or other conventional “prices,” but from fees. For example, prior to the CARD Act (2009), we showed that credit card lenders earned more from fees than from interest charges for low-credit score borrowers.

Source: Agarwal, Chomsisengphet, Mahoney, and Stroebel (2015)

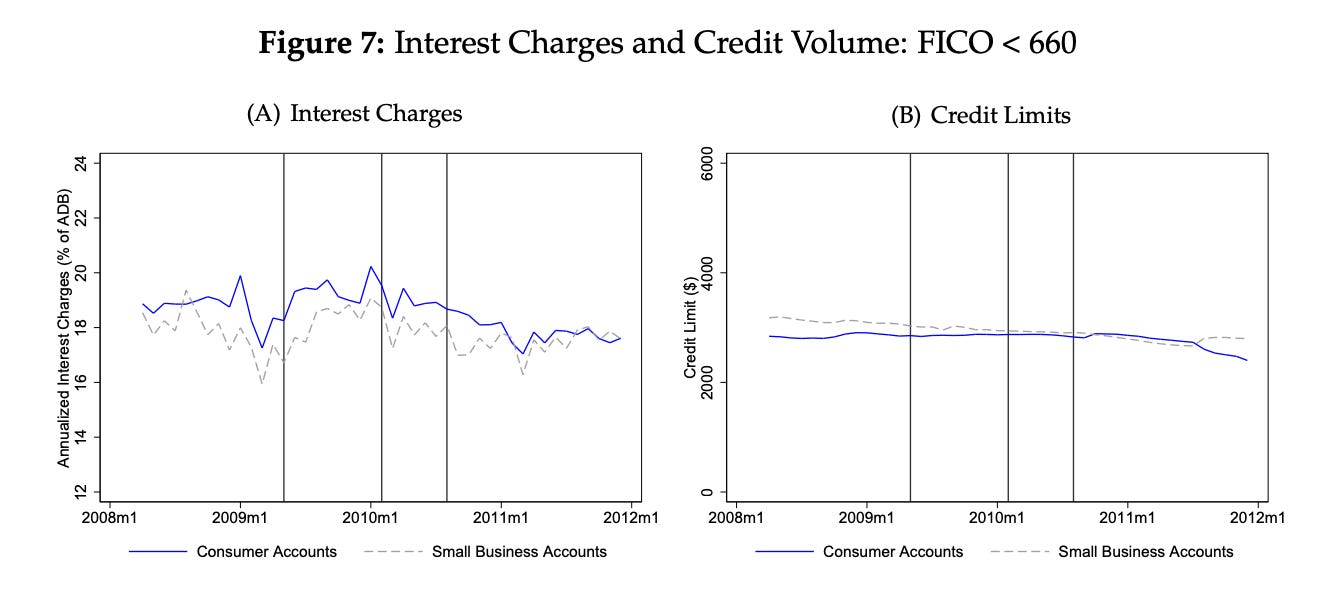

The CARD Act restricted these fees, effectively eliminating over-limit fees and capping late fee amounts. At the time, bank lobbyists warned that any consumer benefits of these fee restrictions would be illusory, offset with higher interest rates and reduced access to credit. However, a difference-in-differences analysis that compared consumer credit cards that were subject to the law to small business credit cards that were not showed no offsetting effect.

Source: Agarwal, Chomsisengphet, Mahoney, and Stroebel (2015)

In the paper, we argued that the lack of offset resulted from the combination of non-salient fees and market power. If the fees were salient, credit card issuers could have reduced fees and raised interest rates, and consumers would have known they were paying the same total price. If markets were perfectly competitive, banks would have had to increase their interest rates or else lose money. However, if markets were both uncompetitive and fees were not salient, then consumer financial regulation could transfer money to consumers. All in all, we estimated that the regulation saved credit card borrowers $12 billion per year.

More generally, my work in this area convinced me of the harms of an industry that was too reliant on fee revenue. Unlike an upfront price such as an interest rate, most fees are hard to comparison shop on. To know how much you’ll pay in fees, you need to know the fee schedule and your likelihood of accruing them, a tall order even for people who study fees for their day job like me.

In addition to their competitive effects, fee-based revenue models impose a disproportionate burden on people I think we should be helping. Rather than being distributed either equally across consumers or according to use, fee-based revenue models generate the most revenue from those who are unlucky or are most likely to make mistakes. Not something that I think is socially desirable.

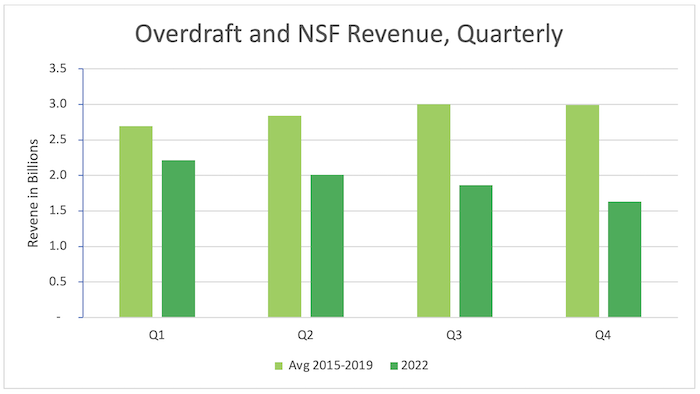

Based on these arguments and others, I have supported the CFPB's efforts to shift the industry away from fees. This includes guidance and enforcement actions against particularly egregious overdraft and non-sufficient fund (NSF) fee practices and a rule that would further reduce overdraft amounts. I have also been supportive of efforts to lower late fees that have since been blocked by the courts.

Source: CFPB

Reducing the credit market burden of medical debt

A second area of strong overlap between my research interests and CFPB actions is medical debt, specifically the reporting of medical debt on credit reports.

Debt collectors are not required to report medical debt to the credit bureaus. Historically, they have chosen to do so because it provides them with leverage: People who see medical debt on their credit reports are more likely to pay, and debt collectors can offer to remove debt in exchange for sticking to a payment plan.

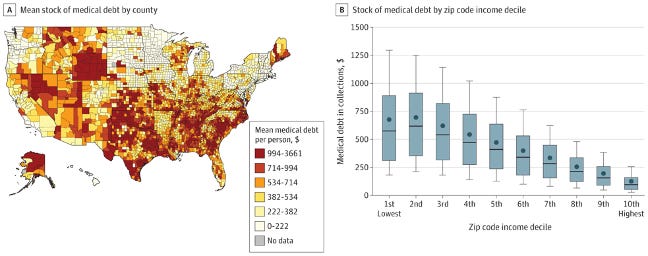

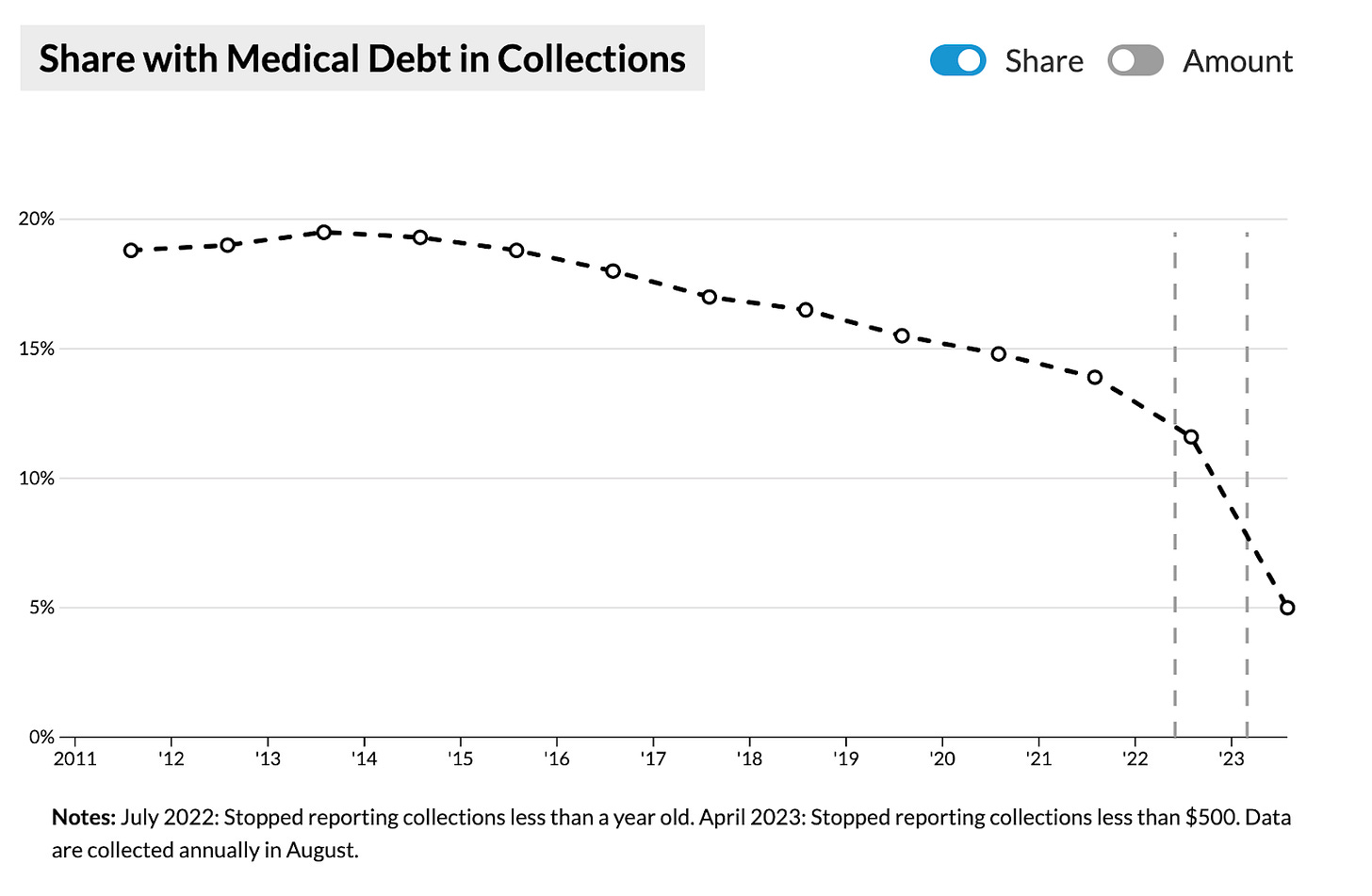

As recently as 2020, 18% percent of adults had medical debt in collections on their credit reports. The rates were particularly high in the Deep South, reflecting those states’ failure to expand Medicaid under the ACA, among other factors:

Source: Kluender, Mahoney, Wong, and Yin (2021)

The debt collection industry argues that removing medical debt from credit reports will degrade the accuracy of credit scores — but that is a weak argument. Medical debt, more than any other form of debt, is the result of bad luck, not bad financial behavior. It thus is a weak signal of future creditworthiness, as a 2014 CFPB report found. While this naturally means that removing medical debt has only a modest average effect on credit scores, removing medical debt has a meaningful impact on those with no other debt in collections.

Given the low signal value of medical debt for creditworthiness, the question of medical reporting boils down to whether we want to provide collectors with additional leverage to recover medical debt. For me, I don’t think this is a valid purpose of credit reporting. For this reason, I’ve been supportive of the CFPB's efforts to remove medical debt from credit reports, achieved through greater enforcement and an agreement with the credit reporting agencies to no longer report debt that was paid, less than $500 in value, or less than one year old. The CFPB has proposed fully eliminating medical debt reporting, although that now looks like it’s on the chopping block.

Source: Urban Institute

Cracking down on scammers

Another core function of the CFPB is to crack down on scammers and scammy behavior. Perhaps the highest profile example is the series of penalties totaling $3.7 billion assessed on Wells Fargo for widespread and repeated abuse.

The case for having a strong watchdog for consumer financial markets is as compelling as any sector of the economy. Consumer financial products are confusing, and it’s not realistic to depend on market forces to discipline bad actors.

Indeed, for non-economists or policy wonks, I think the law enforcement mission of CFPB is the most resonant, and defenders of the CFPB are correct in highlighting the CFPB’s enforcement actions in the media this week. See this thread by Michael Negron or Paul Krugman’s Substack for more.

Will there be a political backlash?

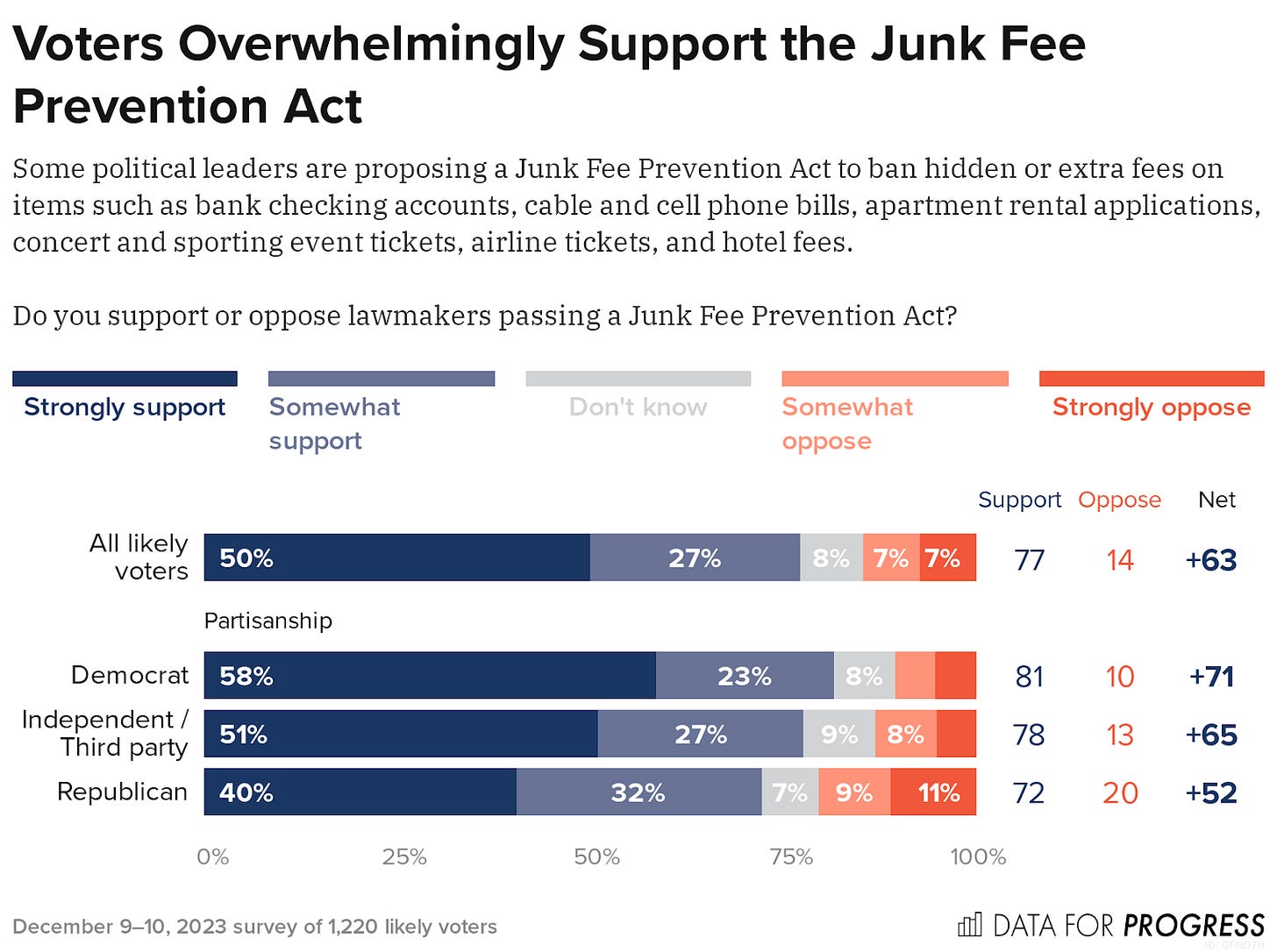

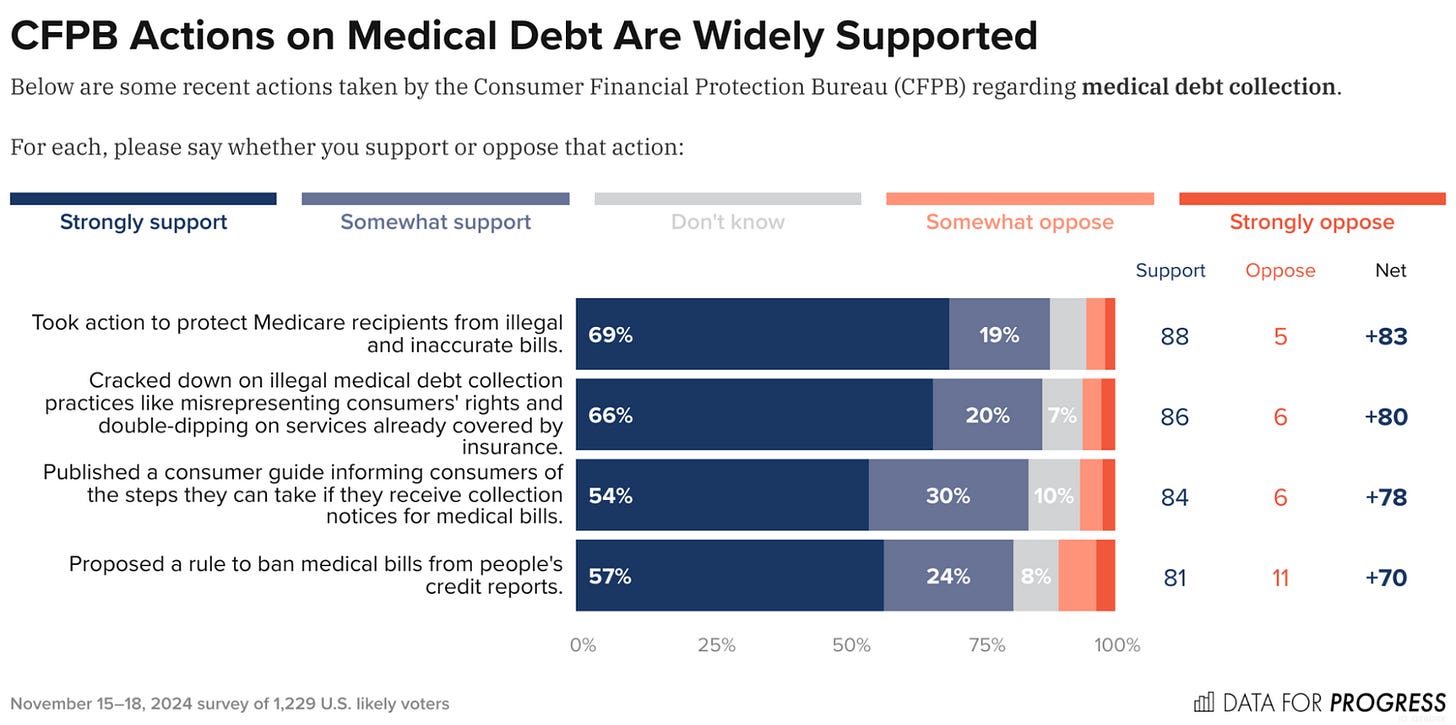

Polling has consistently shown overwhelming support for junk fees and medical debt policy, including the actions taken by the CFPB. I have not done a comprehensive review of the polling, and these numbers may have slipped as the issue has become more politicized, but I think it’s safe to assume that dismantling the CFPB is not broadly popular.

Source: Data for Progress

Source: Data for Progress

There is much we don’t know yet about how this will play out, including whether the courts will step in and whether and to what extent the Trump Administration will ignore or outmaneuver the courts. Ultimately, the most important check on Trump's policy is the voters. If Trump does succeed in dismantling the CFPB, then it will be important for voters to know that every bank fee they receive and medical debt on their credit report has Trump’s name on it. Junk fees are now Trump fees, you might even say.

The #CFPB is super-efficient in its core mission: protecting American consumers from illegal charges and businesses practices, and has garnered a lot of refunds for many consumers. The ‘E’ in #DOGE stand for #Efficiency. So, #Elon, keep your mitts off it!